Finding My Own Sense of Place Through Wine

Story by Adam McHugh

It is said that to open a bottle of wine is to travel the globe without the inconvenience of leaving the dinner table. In liberating that cork, one does not simply increase enjoyment of a meal, but rather takes off on a thrilling journey. The living liquid in the bottle is a portkey to a farm and a community far away, an opportunity to share for a little while in the life of a people unknown. This feature proved especially important for this writer, who found himself overwhelmed by the weight of a career rooted in grief response.

It was a good story for a pandemic lockdown, anyway. Wine can bring the world to us when we can’t go to the world. “I am not a drinker,” you told yourself, “I am an explorer,” you argued as you army-crawled to the back of the wine closet on a Tuesday afternoon.

Coping mechanisms for the apocalypse aside, wine’s power to transport the drinker to other times and places is impressive. One glass can recall memories long dormant or sweep us into unfamiliar country sides. This seems especially true of bottles that exhibit what wine geeks call a “sense of place.”

These wines open a window to a new world, a taste of the vines from which they come. Grocery store shelves are lined with a myriad of labels that reveal little but sameness. But wines with a true sense of place demonstrate a distinctiveness, a sensory signature. They give voice to the effects of the sun and the soil, the air and the water, and all the labor, joy and struggle that brought each vintage to life. This is especially true of California wines and the many vineyards that dot the state’s Central Coast.

The transporting power of wine is, for me, more than a sensory curiosity. There have been times throughout life, even before the pandemic, when wine offered a lifeline to a happier place. It even stirred in me a desire to find my own sense of place.

For many years, home was one the outskirts of Los Angeles, where I spent my nights working as a hospice chaplain and grief counselor. Nights were spent navigating dark L.A. freeways from home to home and nursing facility to facility. I sat at the bedsides of people taking their last breaths and tried to provide a teaspoon of comfort for their loved ones on one of the worst nights of their lives. I listened to and held their questions, feelings, prayers and griefs. It was sacred yet strange work. And, as one might expect, it was emotionally taxing. Compassion fatigue visited often.

Caught in a vacuum of heaviness, I found some levity as a student of wine during those years. Wine courses at UCLA enabled me to study for a sommelier certificate and the certified specialist of wine exam. In tasting a broad array of products for those programs, I let wine take me all over the world – at least in my imagination. But where many of my favorites took me, again and again, was to California’s Central Coast.

As time went on, a mental visit to these wine-soaked places wasn’t enough. I began to regularly flee to the north, sometimes making the 7-hour round-trip in one day. These places were a profound type of therapy for me. When my world back at home seemed to engulfed in death and sadness, these lush landscapes, where mountains crash into seas and vines are stitched into every bucolic hillside, seemed so alive and full of abundance. During my visits to San Luis Obispo County, I would ask these sprawling, open landscapes to open my heart again when the nature of my work had closed it.

As many visited to the Central Coast have no doubt discovered, this region is the sort of places that make you want to change your whole life. A few years ago, after compassion fatigue had finally overpowered me, I left the hospice industry for a job at a winery in the Santa Ynez Valley. This was the beginning of a wine odyssey that took me through several different roles in the wine industry, until I finally settled in as a wine tour guide. Now, I spend my days introducing visitors to the same places that healed my heart. It’s a full circle type of experience that, like the vineyards themselves, involves a seasonal evolution: death, rebirth, and growth.

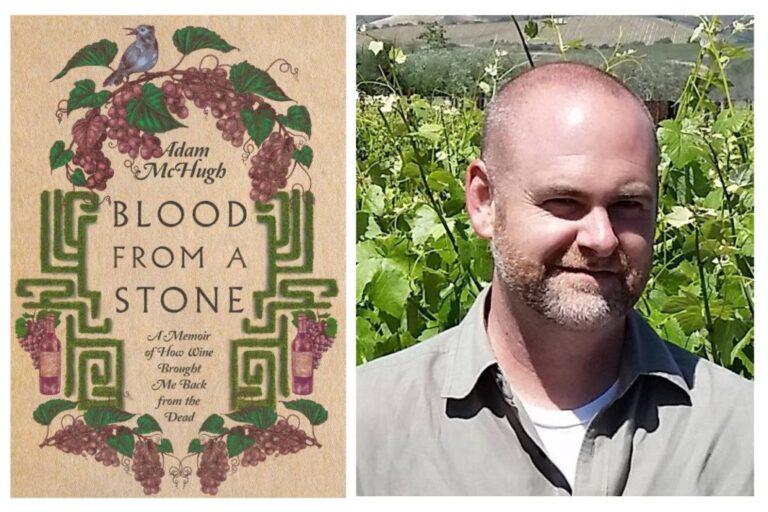

Adam McHugh is the author of the newly released Blood From a Stone: A Memoir of How Wine Brought Me Back from the Dead, that tells the story of how he stumbled his way from hospice chaplain in L.A. to wine tour guide and sommelier in the Santa Ynez Valley. It was a finalist in the Andre Simon Food and Wine Book Awards in London. You can connect with Adam on Instagram @adammchughwine