Going Whole Hog

“You can breed the pigs and buy the corn and get on. You can raise the corn and buy the pigs and get on. If you buy the corn and buy the pigs to feed, you haven’t got a chance.” — Louis Bromfield, Pulitzer Prize-winning novelist, conservationist and farming pioneer.

Diego and Meg are two Gloucestershire Old Spots breeder hogs living their best lives on a vineyard in Creston. Owner Hilary Graves has been raising and selling this heritage breed for more than 10 years on her home ranch. She purchased her first three hogs in 2008 when she came across a photo of the breed in her seed-saving catalog. “I knew I had to have them. We drove up to Marion, Ore. to pick up my boar and two sows. That was my original breeding stock.” The boar ironically ended up being sterile, just one of many complications of small-scale livestocking to consider. No matter. She found a breeder in nearby Aromas and borrowed a boar — “his name was Guapo” — and was quickly on her way. “At one point, I think I had 37 piglets at once.”

I ask why she had stuck with this breed. “I think they’re really exceptional eating. This breed is very long so you get a lot of bacon or pork belly. Heritage breed animals haven’t had all of the really great eating characteristics bred out of them.” Unlike these heritage breeds, industrial pigs are bred to grow as fast as possible. So just one difference is in the fiber and texture of the slower growing muscles and fat. The Gloucestershire Old Spots are known for their docile demeanor and their strong maternal instincts. These are important qualities in a homesteading environment. Piglets, upon birth, are tiny in comparison to their 500-pound mother, and there are generally between eight and 12 in a litter. The mother will try to communicate with them that she is rolling over on her side for them to feed, but tragically, sometimes there are casualties in this basic routine.

The complexities and financial reality of homesteading and small-scale livestocking have worn down the initial excitement of Hilary’s first purchase of breeding stock. The harrowing first few days of basic survival are followed by the daunting and expensive responsibility that all piglets must be vaccinated and the male piglets be castrated within five days of birth. Raising these pigs to a weight of 250 to 300 pounds takes around eight months, and costs Hilary on average $1,000 per pig just for feed, not accounting for veterinary fees, or her own personal time and labor. “My first three pigs, I used to put sunscreen on them every single day. It takes a lot of time.” I ask about the feeding. “I use organic feed. It would be a lot cheaper if I didn’t,” Hilary admits. “It’s just my own observation … The pigs that I raise on organic feed and on pasture, they taste better.”

A while ago, Hilary offered me half of a hog. I’d purchased whole chickens and lambs from her, and when quoted what I felt was a fair price per pound, I was eager to sign up. I pictured something like the pig from Charlotte’s Web, and therefore was completely taken aback when I received the invoice noting its hanging weight of 120 pounds. I remember clarifying that it was, indeed, just half a pig coming my way. I just had no idea how large these animals actually were.

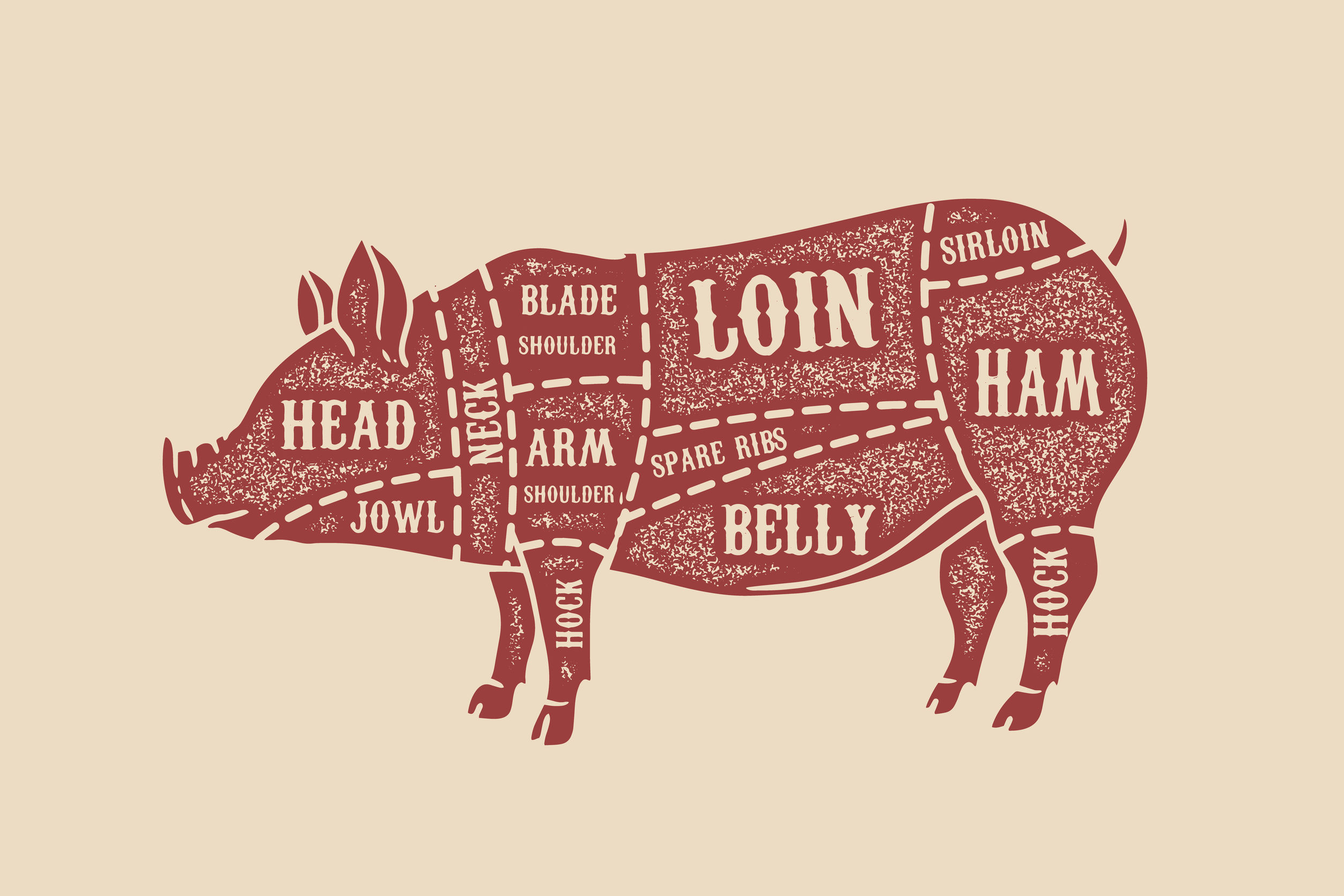

Then I got a call from the butcher asking how I would like my hog cut. “Um … in pieces?” I answered, naively. The butcher very patiently guided me through the myriad of options I had no idea existed. “That’s why I like working with J&R Natural Meats and Sausage,” Hilary says. “The guys at J&R, if you go in and sit down with them, they’ll go over the cut sheet and go through all the different options.”

Thinking back today, I can’t recall exactly what I told them. I remember they were very patient with me. After speaking to a more whole hog-savvy friend, I asked to keep all of the fat to render my own lard, and the bones to use for stock. I requested bacon instead of pork belly. I asked to keep the jowls and other obscure cuts. And I was happy to already be a proud owner of a drop-in freezer as a domestic fridge-and-freezer combo is not a great match to store 100 pounds of pork next to the ice trays, bags of frozen spinach and frozen pizza dough.

Today, standing with Hilary in her pen next to two enormous sleeping hogs, I ask her what she chooses when given these options. “I think as simple as possible is better. I don’t usually do hams … I like roasts instead. I usually have them cut up a few softball or cantaloupe-sized roasts. And I don’t usually do bacon either; I do pork belly. I have southern roots, my Dad’s family is from Arkansas and Oklahoma and I have become fascinated with the idea that really the only cuisine that comes from America is Southern cooking. It’s pretty much poor people eating what they grow, and they use every bit of it. So a lot of Southern cookbooks have great recipes for using whole animals or obscure cuts.” She recommends The Gift of Southern Cooking by Edna Lewis or The Southern Foodways Alliance Community Cookbook edited by John T. Edge, Sara Camp Milam and Sara Roahen.

We discuss the day of harvest. Standing with these adorable creatures in this idyllic spot under the shade of oak trees, it’s difficult for me to use that word, to think of them as an agricultural product. “I’m not saying it’s easy,” Hilary says. “I tear up almost every single time. But I feel very good that it’s not a stressful experience for them.” Looking down at Diego and Meg then out over the surrounding vineyards, and the wildflowers beyond leading down to the pond, I feel good about that, too.