Managing Water to Protect San Luis Obispo County’s Farming Future

Story by Linda Reed

Illustrations by Dyna Beach

“Whiskey is for drinking; water is for fighting over.”

This authorless phrase is often misattributed to notable writer Mark Twain, but nonetheless, it’s a valid argument. Whiskey, and other distilled spirits, beer and wine all require water for production. It goes without saying — the same is true of all agriculture. It’s no wonder management of this vital resource is top of mind for San Luis Obispo County farmers, ranchers, brewers and winemakers.

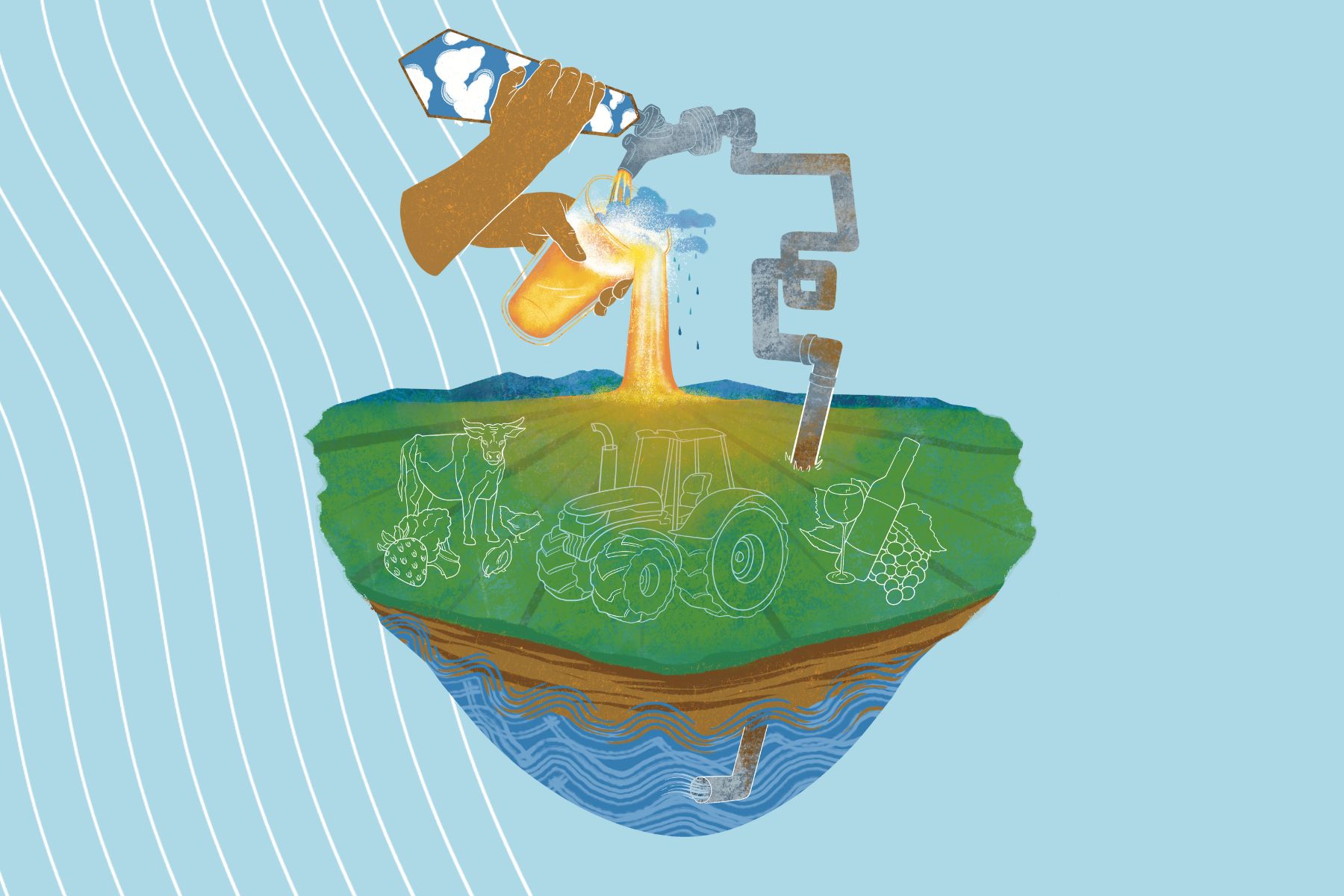

The Water Cycle

The cycle of water is a concept taught in many earth science classrooms: evaporation from oceans and lakes feeds clouds that carry rain. When clouds release their contents, some water seeps into aquifers through percolation, while much of the remainder travels to the ocean via rivers and creeks. Plants and animals use the rest through groundwater.

In dry years, farmers and homeowners pump more from the aquifer to water crops and lawns. Too many dry years can lead to drought. San Luis Obispo County’s Public Works department monitors 26 weather stations that track rainfall across the region. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) monitors data on drought conditions throughout California, where dry years have become more frequent than wet years. Either condition requires farmers and producers to adapt.

Water is Critical to SLO County Producers

San Luis Obispo is well known for its wineries and, increasingly, breweries and distilleries. Beyond what’s in our cups, the county recorded in 2022 its third ever instance of producing more than $1 billion worth of agricultural commodities. According to the local agriculture department, 10 crops account for 75 percent of that total — wine grapes and strawberries comprise nearly a third together. These farming interests compete for water with homes, golf courses, businesses and of course, human consumption.

The water for all these uses comes from seven aquifers spread out throughout the county and in Santa Maria. The Groundwater Sustainability department considers three of them “high priority,” meaning they follow mandatory plans for responsible groundwater management and face stricter regulations regarding groundwater usage compared to low priority basins.

In years of drought, farmers must increase their water usage to irrigate more often. Ariela Gottschalk, Owner and Operator of Halcyon Farms in Arroyo Grande, says water is one of the biggest bills for a farm. “Expenses for electricity to pump water are definitely much higher in drought years,” she explains. “That impacts our profit margins.”

During a wet 2023, rainfall refilled depleted reservoirs in a much-needed way. But one wet year doesn’t remedy decades of drought or replenish aquifers. During the last drought, the Paso Basin Land Use Planting Ordinance limited increases in crop acreage and expansions of well bore diameters, and many of the restrictions remain in place. These guardrails slow farm growth, causing a financial pinch.

Minimizing Groundwater Demands

The Paso Robles Groundwater Plan, which was approved by the state in 2023 and calls for reduced water allocations for agricultural and other uses. This came as the basin experienced a sizable overdraw in the amount of groundwater pumped, which is not sustainable. The over use has caused vineyards and private residential properties to face water shortages in recent years that led to the trucking in of water and expensive drilling of deeper wells.

To lessen the impact, many farmers, ranchers and winemakers have implemented practices that will help conserve this vital resource. Hambly Farms in San Miguel grows native and drought-tolerant trees, plants and shrubs to minimize their impact on the water table. “[We have] added new fields over time,” Gina Hambly explains, “so, as one field matures and needs less water, we can add new fields and maintain water usage until they have matured.”

Planting cover crops and using mulch helps to reduce evaporation. Tilling the soil less frequently reduces soil erosion and greenhouse gas emissions. Livestock grazing, compared to mowing with heavy equipment, improves water quality and also reduces soil erosion. And livestock fertilize as they move around, reducing the need for chemical nutrients. Micro-irrigation or drip irrigation gets water directly to the plants rather than risking transpiration, or the loss of water to the atmosphere.

“We live in one of the most beautiful places in the world, many travel to visit and many wish they could stay,” says Gina. “We need to manage our resources with respect and prioritize food production.”

The county announced in 2024 the Paso Robles Groundwater Basin Multibenefit Irrigated Land Repurposing Program as a strategy to encourage farmers to pump less water from that groundwater basin, starting in mid-2025. The program will offer guidance, technical assistance and, possibly, even financial support to those who want to pivot their farming practices. If the effort doesn’t curb water use, farmers would have to pay to extract water from this basin.

Residents who want to be good stewards of both water and land can utilize tools provided by The State Water Resources Control Board to monitor and learn about usage and management. We all have a responsibility in conserving and protecting our groundwater resources.

Though Mark Twain would hardly recognize the Central Coast today, the push and pull between humans and nature continues. Managing this valuable resource so that we and future generations can live in our little slice of heaven, with the food and beverages SLO county farmers produce, is a challenge — doing so effectively is imperative.

As the famed poet W.H. Auden said, “Thousands have lived without love, not one without water.”