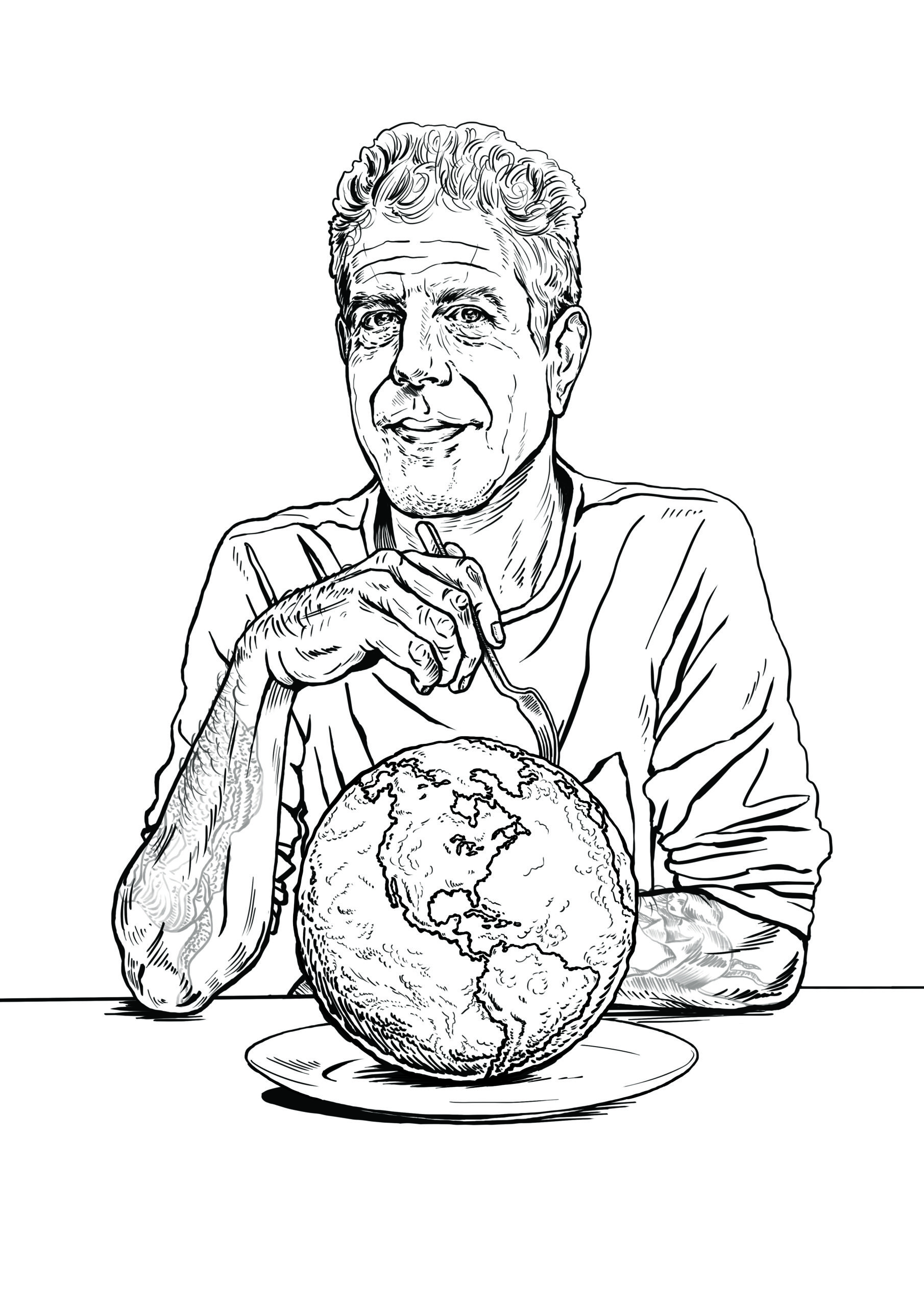

The Point and Counterpoint of Anthony Bourdain

A celebration of his life, on the year anniversary of his passing.

Illustration by Anna Takahashi

A year has passed, but to many of us the death of Anthony Bourdain still feels close. It’s not hard to gather why; as readers, eaters, and tagalongs on his adventures, we grieve the loss of our worldly, gritty guide to parts unknown.

I saw Bourdain once. He was touring after the release of his memoir, Kitchen Confidential, and I happened to be poking around the shop where he was signing books. I remember him as tall and lean, with a wry smirk and dark eyes. He wore an air of cool authority, like that of a rock star, though at the time, he hadn’t yet become a household name. I later read Kitchen Confidential and marveled to learn that he’d attended my alma mater, Vassar College, in Poughkeepsie, N.Y. Bourdain never graduated, opting instead to matriculate at the Culinary Institute of America (CIA) in nearby Hyde Park.

On the day he died, I thought about that chef I’d seen, the one with the posture of a rock star. I also thought of the chef who had left a high-flown liberal arts college to attend the CIA, an institution that drilled the Five Mother Sauces à la Escoffier. Bourdain had the uncanny ability to be both, in all their glorious tension. He knew all the rules, yet had the cojones and skill to break them.

Bourdain was sharp-tongued, to be sure. (“I’m a radical environmentalist,” he once wrote. “I think the sooner we asphyxiate in our own filth, the better.”) But Bourdain’s crabbiness did not eclipse his magnanimity, which brought kind attention to ingredients, people and cultures that had rarely, if ever, been seen outside their immediate environment.

Such care made him a humanist who brought deep empathy and an anthropological interest to the world’s appetites; it didn’t hurt that Bourdain had the artistry and vocabulary to put it all into words. In an interview with food writer and teacher Dianne Jacob, he once said, “When you see what really great chefs cook after work, they make something very simple and heartfelt. It’s evocative of happier or simpler times. It’s the same process when someone who loves you is making it. Chefs don’t want to see technique after hours, they want to submit.”

—

The signs of mental illness often read so similarly to the signs of creativity and passion that no one can tell when someone is suffering. In her essay on mental health and creativity for the 1990 anthology Eminent Creativity, Everyday Creativity, and Health, neuroscientist and psychiatrist Nancy C. Andreasen drew strong parallels between the two. In her famous study of the writing faculty at the Iowa Writers’ Workshop, Andreasen found that 80 percent suffered some kind of affective disorder, as opposed to just 30 percent for the control group.

Later, Andreasen would posit that creativity and mental illness are similar in one key respect: both synthesize and make sense of disparate elements. Think of a sculptor working around a flaw in marble, a composer noodling with dissonant tones to find a perfectly imperfect phrase, a chef combining flavors and textures rarely seen together. The act of connecting seemingly unrelated dots is the hallmark of all great art and ideas.

Sadly, it’s also the hallmark of mental illness. Though an outsider might see Anthony Bourdain as a man with everything to live for ― a thriving media career, a position of respect in the food community, the world’s permission to explore on our behalf ― his own beautiful mind did not. In his writing, he described regular depressive episodes in which he was “utterly depressed … in bed all day, immobilized by guilt, fear, shame and regret … heart palpitations, terrors, bouts of self-loathing …”

There has never been a good answer for why gifted, open, insightful and intrepid people fall prey to mental illness. I think about how a bright flame can light a path or, alternatively, spark a wildfire, how water can sustain a person’s life or end it. The coexistence of creativity and confusion is elemental like that.

Whatever his demons, Bourdain’s gift to us was himself: incongruent pieces brought together and made harmoniously whole, for the betterment of eaters everywhere. He wasn’t “just” a food personality. His work made all of us explorers, ripe with curiosity and ready to submit to the journey. He shone light on dark places, brought attention to the overlooked and whetted our appetite for the great wide open. I only wish he’d stayed longer.

The reminiscing of a legend by the local food community

I loved listening to him read his books on my way to culinary school. I’ve watched all of the episodes of both of his shows, taking notes on places I traveled to and have yet to go. I think part of Tony’s legacy is reminding us, especially now, that food is community. Whether he was taking us to a grandma’s kitchen in a war torn nation, or the kitchen at his bestie Eric Ripert’s Michelin star restaurant, he showed us differences can melt in the kitchen and at the table. I feel I am afforded the opportunity to share his ideas with folks while cooking food, making every day in the kitchen an adventure. Thank you, Tony, for inspiring so many of my culinary adventures here and abroad. You are missed.

— Chef Clare Cranford, The Wellness Kitchen

Bourdain and I are both from the East Coast. As a young boy, he went to school in Englewood, N.J., the next town over from where I grew up. Anthony attended the Culinary Institute of America in New York, as did I. He and I share a quest for authentic tastes and regional specialties. He sought genuine flavors from around the world. When I moved to California in 1980, I embraced the flavors of Central Coast BBQ. Now, sharing the taste of local history with red oak pit BBQ is my passion. Anthony Bourdain’s pursuit of history and cuisine continues to live within me.

— Chef Brian Stein, Stein’s BBQ & Catering

Anthony once said ‘skills can be taught. Character you either have or you don’t have,’ and it could not be more true to how I started my business almost 10 years ago. As an HR manager for a giant clothing company, the last thing you’d find me doing is baking. When my son wanted a cake for his birthday, I YouTube’d a video and made the cake. No fancy pastry school, no culinary arts degree, just a whole lot of experimentation, and now I’m preparing to open my second bakery. I’ve found inspiration in Anthony. Above all else he was relatable, and I’ve been successful because that’s me — totally relatable. I grew up here. I know our community. I respect the customer base here and connect with them on a level others cannot. The way Anthony connected with others was unparalleled.

— Libby Ryan, Just Baked Cake Studio and Bakery