Family Ties: Finding Comfort Abroad

Story, Photography & Video by Aja Goare

In this first-person piece written by Edible San Luis Obispo Managing Editor Aja Goare, she shares how her visit to Germany and the food she ate there helped preserve the memory of her late grandmother.

On a cobblestoned street surrounded by vibrant green forests, halfway around the world, I looked up at the duplex in south Germany where my great grandmother spent her childhood. Years before I was born, my grandmother – Dorothy Goare – had visited this very spot to learn about her mother’s early life. And now, five months after Dorothy’s death, I was doing the same alongside my father and sister.

“The great thing was being able to do away with the myths you have in your head – what must that be like – and of course my grandmother is the one that left and came over on the big boat to find a new way in America,” says my dad, James, reflecting on the trip. “It’s one thing to think about it and the terms you can make up in your head; it’s another thing to stand in the spots and take the pictures and talk to people that were there and knew. That’s a whole different thing.”

In 1912, my then 24-year-old great grandmother Pauline decided to leave her small Bavarian town of Heidenheim for America. Just 10 days after the infamous Titanic sank, she boarded the S.S. President Grant with her half-sister and took a two-week-long voyage to New York. As a newspaper account of the trip explains, she only “brought her clothes and a German Bible.” Upon her arrival, Pauline didn’t speak English and had few connections until she met and married her husband in 1920.

Among the few physical artifacts that remain from Pauline’s time on earth are photos, a newspaper clipping about her nautical journey, and a menu from the boat that included “calf’s head à la Tertolliére” and sardines. She died when my father was just a boy, but he holds dear those young memories of his grandmother.

“It felt like a time capsule. The town felt exactly as it would have if our grandma was still there. It didn’t seem like it had changed much but in the most beautiful way.”

Jasmine Goare

Among the few physical artifacts that remain from Pauline’s time on earth are photos, a newspaper clipping about her nautical journey, and a menu from the boat that included “calf’s head à la Tertolliére” and sardines. She died when my father was just a boy, but he holds dear those young memories of his grandmother.

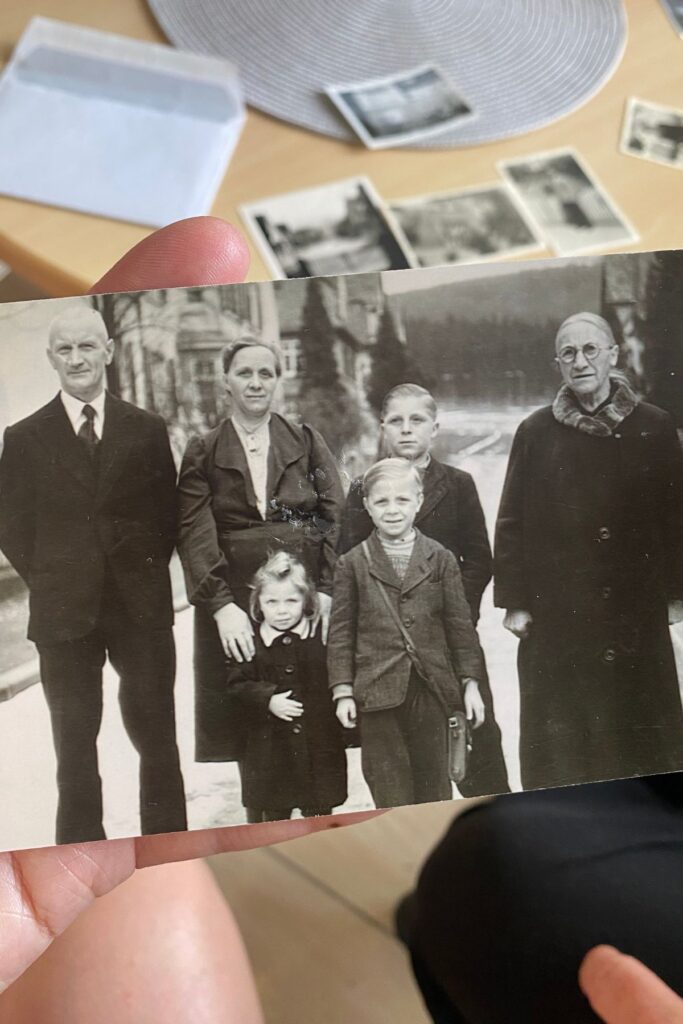

When anyone we love passes away, we find ourselves clinging to their worldly objects – a sweater, rings or watches, a keepsake – for a sense of comfort. My grandma Dorothy was a private woman who kept a lot of her memories behind lock and key in her mind. In her absence, there aren’t many family stories or heirlooms to hold on to. But on our trip to Germany, a meeting with a cousin we’d never before met presented us a trove of photos from the lives of my grandmother and great grandmother, long before us.

“That was crazy, especially because there were photos of dad as a baby that I didn’t know existed and he has a really small amount of pictures and memories,” says my sister, Jasmine. “Seeing that was really special, because it was history I didn’t know about and just seeing new things – I’m very sentimental.”

Swapping stories with our German relative over a plate of spaetzle, overlooking the city of Heidenheim, we three Americans relished every account. That includes one where Pauline, who was already 76 by the time my father was born, stole the show at her sister’s bridal shower by appearing in a flashy red dress. “No way, Pauline did that?!” my father asked our cousin, Jochen, in disbelief. “She did, she did,” Jochen said with a laugh in between bites of his beef rouladen, a traditional German dish featuring long, thin strips of meat slathered with mustard and filled with bacon, onions and pickles. Digging into my semmelknödel – a tender dumpling made from stale bread, milk, eggs, onion and parsley, soaking in a rich gravy – I glanced up at the Helenstein Castle that stood before us and wondered if my great grandmother had once shared this same view.

After pouring over photos and swapping stories, we tucked in for the night at our rental, exhausted from the travel and time change but exhilarated by all that we’d just learned and the town we’d just explored.

“It felt like a time capsule,” recalls Jasmine. “The town felt exactly as it would have if our grandma was still there. It didn’t seem like it had changed much but in the most beautiful way.”

The next morning, Jasmine and I wandered the hilly, winding streets of Heidenheim and landed at a bakery where we ordered coffee and an assortment of pastries. With only the soft sound of mist landing on vines, I bit into the slice of cheesecake I’d selected for breakfast. Dense and creamy like a slab of brie cheese, it was the best four dollars I’d ever spent. My sister devoured her monkey bread and we briefly questioned if we should turn around and march back in for seconds, before ultimately heading back to wake my dad.

We met with Jochen at a local senior living center. There, we met one of our great grandmother’s first cousins, Annalise. At 94, Annalise is living with dementia but still clings to some sacred memories. We found her in a wood-armed chair, draped in natural light inside the foyer.

“Hallo,” she greeted us with a toothy smile.

“This is my grandmother,” Jochen told us, as he introduced us to Annalise in her native German.

Jochen revealed the box of black and white family photos to his grandmother and for the next 90 minutes, we shared laughs and stories, using Jochen as a translator. Though some faces eluded her memory, Annalise recounted interactions with our grandmother and great grandmother with bright eyes and a warm smile. “She looks like Pauline,” my dad whispered to me.

At the end of the visit, we embraced one another like the long-lost family we are. A few photos captured the moment, which I’m told still resides in Annalise’s memory. “You must have made quite the impression on her,” Jochen said to me days later in text.

These shared moments consumed our conversation over the next few days and well after the trip ended. At a beer garden in Berlin, we recounted the time spent with Jochen eating ice cream and wandering the streets, happening upon the golden plaque that memorializes his paternal grandmother who was murdered by the Nazis. “To think [the Holocaust] happened 20 years after Pauline left, she must have been so worried about her family back at home,” my dad thought out loud. It was a lot to unpack.

Despite these two women in our family being gone from our lives, we felt so close to them sitting together around the table and sharing what we imagined were some of their favorite foods. We couldn’t help but feel grateful for the trail of breadcrumbs they left behind that led us to this place and to meet relatives who could give us a sense of communion.

“There are two different lives going on in two very faraway places and they intersect with a few people. It’s funny that they knew our lives and we knew some of theirs,” says James. “When you get together with people that far away, you realize people are people and friends are friends and even though they may talk differently, even though they’re very different people than us – they’re German and have different sounds to their languages, people are people.”