Chinatown For A New Generation

Story by Dakota Kim

Photography by Mary Lagier

Publisher’s Note: We here at Edible Magazine San Luis Obispo are honored to have this feature place in the 2022 Best of Edible Awards. From the best stories and recipes, to photography and illustration, each year the Edible Communities’ network of 80+ publications across the US and Canada submit their work, representing the best content that appeared in our magazines in 2021. And we are proud to say, we placed in the top three of not one, but two categories: Best Feature, and Best Profile Photography. To view all of the winning entries, visit here.

They arrived in 1874 in San Luis Obispo, having survived the long, sickness-inducing boat ride from China’s Guangdong Province to San Francisco, then several hungry months washing dishes while dozing uneasily in a packed boarding house and finally, a cold, foggy schooner trip from San Francisco to SLO. Setting their eyes upon the shore, they followed the other laborers as they walked to the one place that would sell them essentials: the Ah Louis general store. They needed food they knew how to cook, employment to pay for that food, a place to rest their head, a hideaway for their money and maybe opium to mask their homesickness and sore muscles at the end of long days constructing the railroads of the Central Coast.

If this sounds like an epic saga for the storybooks, that’s because it is – and it’s a story that still lives on in two particular buildings, one mural, and one sign.

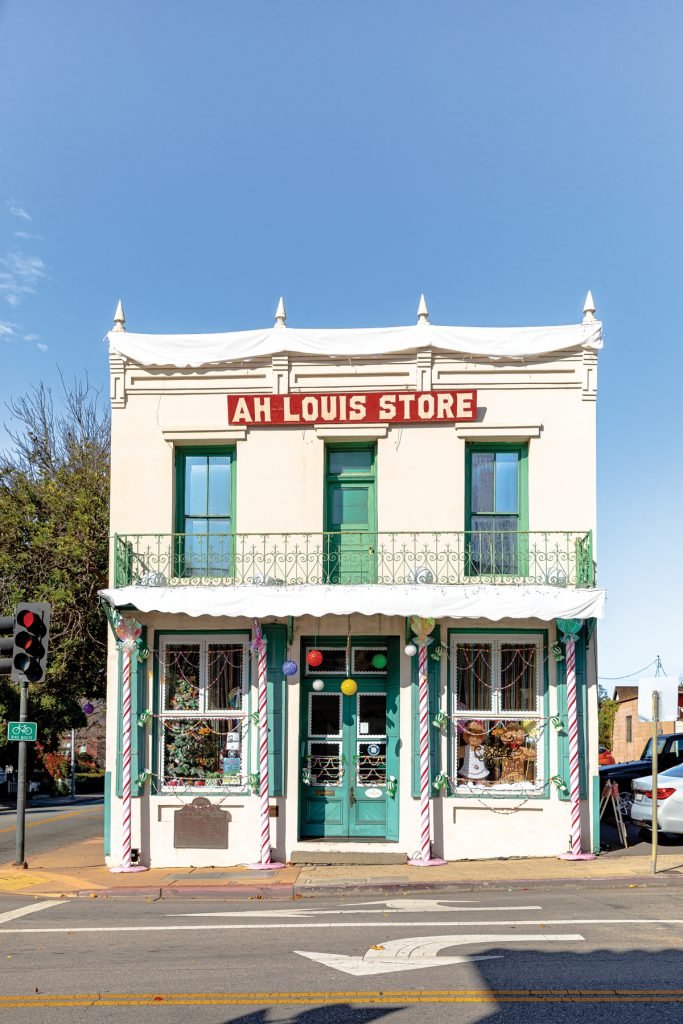

Today the history of SLO’s Chinese immigrants lives on through a few remnants of once-thriving Chinatown. There’s the Mee Heng Low restaurant at 815 Palm Street, marked by the banner proclaiming, “Chinese Noodle House.” There’s the two-story beige building with green shutters at 800 Palm Street, its sign noting “Ah Louis Store.” In the adjacent parking lot, there’s a wall, ornamented by artist Peter Ladochy, with the words “love” and “double joy” in Chinese lettering. Next to it, a plaque declares that the neighborhood Chinese “faced prejudice and exclusionary laws, but rose above such obstacles to make major contributions to local commerce, agriculture and industry,” and the community peaked in the late 19th century.

According to the book, In Search of Chinese San Luis Obispo, the new Chinese-Americans called their little piece of this city “Tong Yun Fow,” or “Chinese People’s City.” The community grew, fluctuating between 200 and 400 between 1870 and 1900; by the early 1890s the Chinese-Americans comprised one in 10 SLO residents. But growth stoked fear, and in 1879 during a statewide election, all but five SLO voters opposed Chinese immigration.

In 1880, the San Luis Obispo City Council ordered the removal of all Chinese laundries within city limits, ostensibly due to steam and odors. In 1882, the federal Chinese Exclusion Act was passed, denying Chinese citizenship and limiting most immigration; it did not end until 1943. According to local journalist and historian Dan Krieger, speaking to New Times, in 1920 there was still a small Chinese population in SLO of 200 to 300 people, but during and after World War II, most left.

SLO Chinatown was dedicated as a historic district in 1995, and one famous character of the district stands above the rest. His name bears witness, emblazoned across the building on the corner of Palm and Chorro: Ah Louis.

Many residents know who “the mayor of Chinatown” was, or even met his youngest son Howard “Toby” Louis, who managed the store until the late 1990s and passed away in 2008 at the age of 100. Ah was born in the Guangdong Province, a southern coastal province from which most of California’s railroad workers immigrated. He gambled on the Gold Rush and came to the U.S. in 1861. Finding no gold at the end of the rainbow, Ah settled in SLO as a cook. It was as a labor contractor and merchant that he found his true calling. By bringing Chinese-American workers from San Francisco to the Central Coast, Ah’s expert dealings fueled the growth of the Pacific Coast Railroad — and of SLO’s Chinese-American population.

And once these new residents arrived, they needed to shop, they needed entertainment and they needed to eat. Thus, the Ah Louis store was born, providing groceries like rice, sugar, tea, rum, sea cucumbers, salted duck eggs and dried abalone. According to Cal Poly archives entitled The Louis Papers, Ah was also responsible for contracting employees, from onion farmers to dishwashers, throughout the Central Coast.

Howard recounted his remembrances of the “Chinese school, wash houses, temple and gambling dens” in what was once one of the largest Chinatowns of the West, numbering 1,500 residents by the early 1900s (though at least 10,000 workers are believed to have passed through SLO). “His family, like other Chinese families, settled on Palm Street because they weren’t welcome a block away in the small adobe shops that flanked the Mission San Luis Obispo downtown,” the Los Angeles Times recounted.

“We had to mind our Ps and Qs, I can tell you that,” the then 91-year-old Toby told the Times. “There was a lot of anti-Chinese sentiment here over the years.”

But within the community, an entire life could be lived. After finishing work on one of Ah’s eight vegetable, grain or seed farms near SLO, which totaled 3,500 acres, at a local laundry or on one of the railroad projects, a laborer could do everything in Chinatown, drink, eat, shop, send letters, manage finances, job hunt and practice religious rites at local temples.

The other prominent SLO Chinese-American family has a more modern provenance. The Gin family, for several generations, owned and operated the famous Mee Heng Low restaurant across Palm Street. Mee Heng Low Cafe was built in the late 1800s, though by whom it is unknown. Gow Gin bought the business and wood building from his cousin, Gin Jack Keen, on October 13, 1945. The restaurant served egg foo yung, egg rolls that were deep fried, battered, then deep fried again, and spare ribs that Anna and Johnny’s child loved, stacking up the bones to create a “Great Wall of China” out of them. (Andrew says his favorite dish is the egg foo yung, because his grandpa taught me how to make it.)

In 1948, Gow’s wife Peggy and their son Johnny began to help him as the business grew. Meanwhile, Gow, Peggy, Johnny and a cousin lived upstairs in the small apartment above Mee Heng Low. Billy Gin, Johnny’s sibling, came to SLO in 1951 to assist with the restaurant. Johnny’s wife Anna arrived in 1956, and in 1959, Pat Gin, Billy’s wife, also arrived to assist in the business.

Once upon a time, Mee Heng Low was not the only restaurant on Palm to supply locals with Chinese cuisine. Chong’s Chop Suey Restaurant, built by Addison Chong in 1923, sat across the street from Ah Louis on the corner of Chorro and Palm. Mary, Addison’s wife, entertained and fed SLO residents at her “high class cafe” for 25 years. One of 12 brothers and sisters, Addison and his siblings had grown up working in their parents’ Chinese grocery on the 800 block of Palm between Chorro and Morro, now the Palm Street parking garage.

In 1932, Shanghai Low opened on the north side of Palm Street, its name inspired by the fashionable 1913 San Francisco restaurant owned by Dai Wah Low. By 1934, according to records compiled by historian James Papp of Historicities, Chinatown restaurants included Mee Heng Low, Shanghai Low, Chong’s, and per the Telegram-Tribune, Lew Gin’s New China Cafe. By 1939, the City Directory lists Chong’s Chow Mein at 798 Palm, Mee Heng Chop Suey Shop at 815 Palm, P.I. [Philippine Islands] Restaurant at 846 Palm (part of the Philippine hub in Chinatown), Shanghai Low (W. H. Harry, manager) at 830 Palm, and the Gold Dragon Café at 985 Monterey, outside Chinatown. By 1950, Chong’s Café, Mee Heng Low, Shanghai Low Café (Gin Koon), and Gold Dragon are listed in the directory.

In 1950, Addison’s brother Richard converted the restaurant into what would become the beloved and legendary Chong’s Home Made Candies, adored by locals and visitors roadtripping through SLO. Having worked at Austin’s Candy Store on Monterey Street, he eventually purchased Austin’s old equipment and opened his own store. Sitting behind the counter in his pinstriped overalls, he provided for sweet tooths for 28 years, until his death in 1978.

According to a November 28, 1974 Telegram-Tribune article by staff writer Bob Anderson, Richard would get up every day at 6 a.m. to go to the shop and cook his candy, including scotch kisses, caramels, rocky roads, nut rolls, toffees, nougats and chocolate-covered nuts. Chong recollected that Palm Street was once a crowded dirt road with wooden sidewalks. “You’d walk up the street and it’d be elbow-to-below.”

Older SLO residents like historian and columnist Dan Krieger recall chop suey and chow mein-flavored ice cream sodas from their childhood; Krieger says the chop suey soda was based on tutti frutti ice cream. These remarkable fusion items display an impressive ability on the part of the local Chinese-American community to adapt and innovate food to the local palate while adding their own flair.

The old wood Mee Heng Low building was demolished in 1957, in order to build a modern two-story structure that included a small apartment housing various family members and, from time to time, the restaurant’s cooks. In 1981, it was remodeled to bring it up to fire code.

On Thursday, April 2, 1981, Mee Heng Low reopened to much local fanfare. “I don’t think that we could have imagined that so many people from San Luis Obispo would have missed Chinese food so much,” Mike Gin wrote in the Mee Heng Low Gin Family Cookbook, noting that the family was grateful for the return of locals. “I can remember that we had long wait times, with customers lined up on the stairs, next to tables and outside.”

Andrew Gin, Mike’s nephew, is proud that so many residents fondly remember the Gins’ Mee Heng Low operation. “Learning about all the former patrons of the restaurant has been amazing. Many people say this was their go-to restaurant. People recall specific experiences they’ve had at the restaurant to this day. The restaurant provided for three Gin families and their children, as well as all of the employees they hired over the years.” The family continued to run the restaurant until Gow and Peggy Gin retired, and Mee Heng Low was sold in August 1988.

Mee Heng Low reopened under new ownership and operated for 20 years under the Hyun family before the business was purchased in 2008 by Paul Kwong, though 815 Palm Street is still owned by the Gin Family.

The Gins and the Kwongs have a close connection — Cody Gin and Russell Kwong, the 20-something members of both families, are best friends. With one as the owner of the building and the other as the owner of the restaurant, Mee Heng Low seems primed to survive the pandemic. But the Kwong family, who purchased the restaurant in 2008 and reopened it in 2009, is struggling to keep Mee Heng Low afloat during this economically challenging time, says Russell.

In its many historical incarnations, Mee Heng Low bears witness to the Chinese diaspora and the Kwongs have written yet another page in its storied history. Paul, Russell’s father, is a lifelong chef who had always wanted to open a noodle house and incorporate family recipes, particularly those of his chef mother. The restaurant’s twice-cooked pork is an homage to her.

“I enjoy being at the restaurant — it’s a really cool place, and I’m emotionally invested in it so we want to get through the pandemic,” Russell says. The Kwongs have expanded the menu, adding smoked ducks for pre-order, as well as hot and sour wings, shrimp noodle cakes, pot stickers and bao, or steamed buns, featuring BBQ pork and spicy black bean tofu.

With his father Paul retiring and the pandemic affecting their bottom line, Russell says he is prepping, cooking and serving almost everything, which leaves little time for innovation these days. Still, Russell questions whether serving classic Chinese-American chop suey is the best business strategy, especially when faced with competition from new cafés offering trendy Asian street foods like Korean tacos and okonomiyaki. Russell says that to reach a larger audience and do something fun, he started serving pork buns at Liquid Gravity Brewing Company.

“I’m not sure how much people even like traditional American Chinese food at this point anymore,” the young restaurant owner muses about the legacy he’s inherited. “Everyone likes it, but it’s not as relevant as it used to be. But I might serve egg foo yung again just to humor myself.”

Beyond its living food history, Russell, who grew up in SLO, would like to see his hometown honor its Chinese-American past with a museum. “Obviously, you can’t restore what’s completely gone, but I think there should be a museum.”

Russell suggests that the railroad district receive a statue of Chinese-American railroad workers at its roundabout, complete with informational plaques. “We should know about our history — you shouldn’t have to work for it to learn about it. I don’t think (Chinatown’s) history is important to the majority of our local government.”

Russell says that confused Chinese and Chinese-American tourists often come to Mee Heng Low to ask where the Chinatown is — and he has to tell them they’re looking at it. He hopes that a future restoration of Chinatown could cater to such tourists with an authentic look at one of the largest Chinatowns on the West Coast, without being owned by outside corporate interests. Russell notes that various SLO Chinatown artifacts, including opium pipes, knives and bones, used to be housed in a small town museum.

“Chinatown is all but demolished,” he says. “The sign on the corner says, ‘Now Entering Historic Chinatown,’ but there are three buildings and a hotel, so it’s kind of ironic.” Ah Louis is synonymous with Chinatown, but there were thousands and thousands of people living here. What happened to them and what were their lives like?”

Unfortunately, so much of what we could know about the eating, drinking and daily life habits of the 19th and early 20th century residents of SLO’s Chinatown has been obscured by mishandling of archaelogical artifacts, which were examined at Sonoma State’s Anthropological Studies Center, including evidence of Native American dormitories from missionary times that pre-dated Chinatown.

Archaeological digs have unearthed gorgeous and historically significant pots, as well as waste pits and animal bones that would tell stories of how Chinese-American SLO residents ate and lived.

Archaeologist Caitlin Chang wrote a master’s thesis at Sonoma State about the foodways of the SLO Chinatown area, funded by the San Luis Obispo County Archaeological Society (SLOCAS) with the potential of using the collection for educational purposes and future outreach.

Chang’s thesis focused on the archaeological remains from a refuse pit associated with the Chong Family, who lived where the parking garage is now on Palm Street from about the 1890s to the 1920s. Chang examined small cut marks on cow or pig bones in her lab, trying to ascertain whether the bones were butchered with a handsaw or a cleaver. By examining these marks, she concluded that pigs were most likely being raised in the backyard by the Chong Family, or their neighbor Ah Louis, and then butchered at home, while beef was most likely purchased at a butcher shop.

“During the early 20th century, handsaws were more commonly used by Euro-American butchers, but cleavers were – and still are – the preference for Chinese cooks,” Chang says. “In my research, I found that pig bones were butchered mostly with a cleaver while cow bones tended to be butchered by a hand saw.”

She was also able to learn that after the 1930s, Addison Chong’s restaurant, located at 798 Palm Street, obtained their smoked pork from a non-Chinese butcher. Chang hypothesized that this change may have been due to the dwindling Chinese population and the decline in local urban animal raising.

Chang found many imported Chinese ceramics featuring iconic designs like the floral “four seasons” motifs, delicate celadon tea cups, and heavy utilitarian brown-glazed stoneware that held a variety of Chinese sauces. “One of my favorite pieces from the refuse pit is a ceramic wedding cake topper of a groom in a long tailcoat and top hat,” Chang says. “It was likely a keepsake from when one of Chong’s children grew up and got married. It’s a great reminder that each artifact adds to the larger story of how an early Chinese-American family incorporated various traditions.”

The future of these items, without a permanent home, is uncertain. Chang’s classmate Lauren Carriere, who has written a master’s thesis focuses specifically on how the Chinatown collection could be used for outreach and a display at the Palm Street Parking Garage. For now, the collection has now been returned to SLOCAS for proper storage and awaits future researchers.

Besides the archaeological bumbling, Chinatown’s history has suffered after important sites were demolished. Caltrans destroyed an old Chinese cemetery to build a new highway in the early 20th century, Krieger told New Times, and in the 1940s, SLO’s government demolished most of the wooden structures on Palm Street, which they deemed run-down fire risks. The Shanghai Low restaurant was demolished by the city in favor of a second parking garage.

“It’s sad to see Chinatown disappear,” Andrew Gin says. “We’re fortunate that the Ah Louis building has been deemed historic and that Karson Butler Events embraces the rich culture of the building.”

The future of Chinatown is uncertain. Copeland Properties has constructed a significant retail development project on both Monterey and Palm streets, including a luxury boutique hotel. At Hotel SLO, a neon Chop Suey sign from Shanghai Low guides diners to a modern hotel bar called S. Low, which the hotel chose as a name to pay tribute to Chinatown’s history, along with an entrance sign symbolizing the Chinese Moon Gate and an entryway made out of stucco and terra cotta baguette tiles.

It’s a far cry from the Chinatown of Ah Louis and Gow Gin, but Russell hopes that in the future, we’ll not only know there was a Chinatown, but also know about the lives of its residents, past and present.

“This restaurant has become my home,” Russell says. “I’m emotionally invested in this neighborhood. We need to put in a historical effort to preserve what’s left of it, and honor what’s gone.”

Andrew Gin agrees. “It would be great to see a Chinese museum emerge in one of the Hotel SLO empty spaces. The work of Chinese people in America and San Luis Obispo is a rich history that should be taught.”

* * *

Mee Heng Low’s Egg Foo Yung (makes 9 patties)

By The Gin Family

This was one of the restaurant’s most popular dishes, in part because of the gravy made with the drippings from the BBQ pork that slow-cooked in the oven for 1–1½ hours. Here, it’s a quicker version of the gravy.

INGREDIENTS

For the egg patties:

1 celery bunch

4 to 5 large eggs

Vegetable oil

For the gravy:

1 14.5-ounce can chicken broth

2½ tablespoons oyster sauce

½ teaspoon chicken bouillon

Salt, to taste

1 to 1½ teaspoons cornstarch

¼ cup water

PREPARATION

Step 1

Grind celery through a meat grinder or a food processor to medium coarseness, not too fine. Squeeze out some moisture and let it sit in a colander. After 30 minutes, squeeze as much liquid out of the celery as possible and place in a large bowl. (We used to use an old press at the restaurant, but since we don’t have that anymore, we just smash handfuls at a time.) There should be just a little moisture left in the celery.

Step 2

Pour vegetable oil into wok until it’s about 1/3 full. Warm over medium heat. While the wok is getting hot, mix 4 eggs with the celery. Stir it gently. Add a 5th egg for a creamier texture and slightly heavier patty. Once the oil is hot, put approximately 1/3 cup of the mixture into the hot oil. Cook on one side. Once it starts to firm up and turn brown, flip the patty. Repeat with the remaining mixture to make the rest of the patties. Remove the patties when brown on both sides, and place on paper towels.

Step 3

To make gravy, mix chicken broth, oyster sauce and chicken bouillon together. Bring to a boil. Sprinkle in salt to taste. In a separate bowl mix cornstarch with 1/4 cup water so it is a liquid. Add the cornstarch mixture to the boiling sauce to thicken it. After about 1 minute, turn the heat down to low until ready to serve. Plate the patty with gravy atop.